Messier Objects

So, you have a telescope or a pair of binoculars and you want to get started in astronomy. One of your first questions will certainly be, “what are the best things for me to look at in my telescope?” Let me introduce you to the Messier catalog. It is essentially a Top-100 list of the most beautiful objects in the night sky. What the Messier catalog is and how it came to be is an interesting and ironic tale.

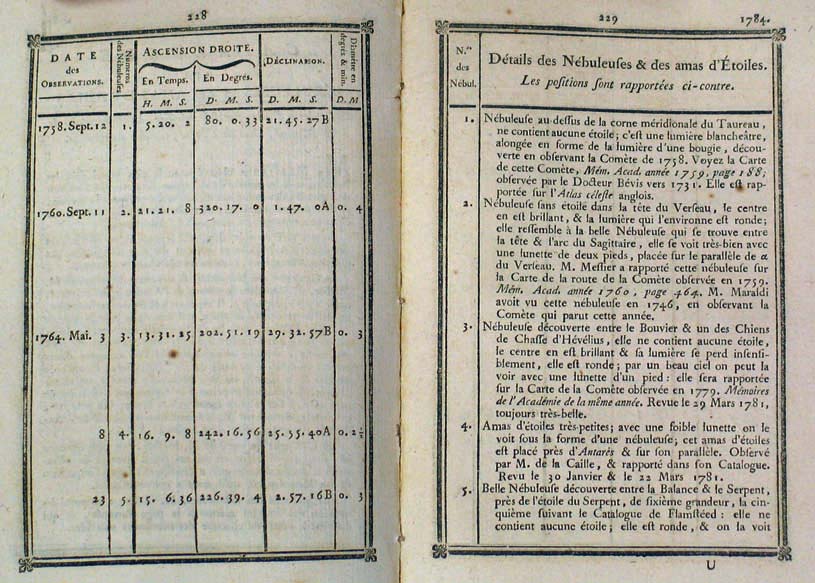

Charles Messier was a French astronomer who lived in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Messier’s specialty was observing comets, fuzzy dim objects that sometimes appear and move across the sky for a few weeks or months, only to disappear again into the blackness of space. You may be familiar with some of the more famous comets such as Halley’s comet, that become bright enough to view with the naked eye and often exhibit a distinct ‘tail’ of gas and dust as they pass through the solar system. Most comets, however, remain more elusive. They appear as fuzzy dim patches in a telescope. Scanning the sky with his telescope looking for comets was Messier’s chosen pursuit. As it turns out, the night sky is full of things that appeared in Messier’s telescope as fuzzy dim patches on the sky. In his search for comets, he would come upon these diffuse doppelgangers which pretended to be his prey. However, after repeated observations Messier was able to tell that these objects were not moving across the sky like a comet, but stayed fixed at the same location against the background of stars. Messier dutifully recorded these ‘not comets’ in a catalog so as to keep himself and others from being repeatedly fooled. By the time of his death, Messier’s catalog of things not to look at through his telescope numbered 110 objects. Ironically, with over 200 years of technology improvements even a modest back yard telescope today reveals most of Messier’s objects to be not just fuzzy blobs, but the most spectacular views in the night sky! (With the notable exception of M40, in my opinion. If I could go back in time, I would remove it from Messier’s list and add the Double Cluster in its place.)

After getting their start viewing the moon and planets, most beginning amateur astronomers hone their observing skills by finding and observing the Messier objects, or M-objects as they are commonly referred to by their catalog numbers. One popular example is M13, a spectacular globular cluster in the constellation of Hercules. M31 is the nearest galaxy to our own Milky Way, the Andromeda galaxy, another must-see on the list. The Astronomical League even offers a Messier Observing Program for astronomers who wish to hunt down and make written observations of each M object. Upon completion, successful observers earn a certificate and a pin recognizing their effort. But, make special note of the rules:

Since the purpose of the Messier Observing Program is to familiarize the observer with the nature and location of the objects in the sky, the use of an automated telescope which finds the objects without effort on the part of the observer is not acceptable. 'Automated telescope' also includes the use of digital setting circles where a read-out shows the user directions to follow to locate an object. This also includes the unacceptable use of smartphones that use apps to locate objects in the night sky. The use of the setting circles found on the axis of telescope should also be avoided. In short, only finder scopes, Telrads, or Telrad-like devices are acceptable.

Computerized telescopes are considered cheating! For those working on their Messier certificate from the Astronomical League, printed charts are the way to go. I have spent many nights under the stars with books and paper charts hunting for Ms. I have packed up many pages soggy with dew in the morning, and stumbled over many books and binders in the dark. Wouldn’t it be nice, I thought to myself, if all of these Messier objects were printed on the planisphere that I always have with me when observing. On the popular planisphere I used in those days, some of the Messier objects were included on the star chart, but most were not. I eventually went to an office supply store and purchased some adhesive ‘dots’, which I marked with the appropriate numbers and stuck to the star chart of my planisphere. But it was not long before I needed a cheat sheet to remind me what kind of object was represented by each of those numbered dots. My cheat sheet eventually adorned the back side of my planisphere with the help of some packing tape. All was well until I tried to work my way through the Virgo galaxies. Overlapping dots were little help in this crowded region of the chart. A special star chart of the Virgo region ultimately made its way to the back, courtesy of more packing tape. And so I went for many years, happily observing Messier objects, often with only the help of my frankenstein-planisphere. There were minor improvements made here and there until it became a perfect observing aid for me. Eventually I decided to design an entire planisphere from scratch, with all my Ms, cheat sheets, and special charts included. The result is the Messier Observer’s Planisphere. I designed it for my own needs, but many other astronomers have confirmed that they find it useful as well. I hope you spend many gratifying nights under the stars with it viewing the Messier objects. All one hundred and ten of them are on the chart, with a grab bag of other interesting objects thrown in for good measure.